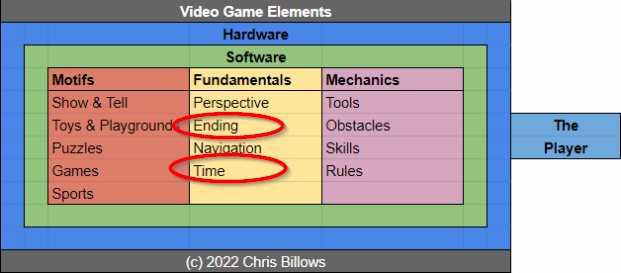

Video Games are many things, but some things are more fundamental than others. As discussed in the previous post, Fundamentals are the engineered layer of game development that cuts across Play Motifs and Mechanics.

This post is a part of the Heropath Thoughts series and will discuss the second set of Fundamentals based around time which completes the spacetime grouping that I’ve nicknamed PENT (Perspective, Endings, Navigation, Time).

Let’s start with the most objective element, that of Time.

Time:

When I talk about Time as a Game Element I see Time having two sub-aspects: Pace and Length. I will define and discuss Pace first and then below define and discuss Length.

Pace – This is the speed at which the player participates in the video game. There are three kinds of Pace:

- Turn-Based. Players take consecutive turns at playing against each other as found in board games like Chess and sports like Golf and Bowling. Players share the same field but indirectly compete against each other with their own objects on their own turn. In Golf and Bowling players each have their own ball and in a board game like Chess, each player has their own pieces they move. Video Game example: Sid Meier’s Civilization series.

- Real-Time. Players are simultaneously playing against each other as found in sports like Soccer/Football, Hockey and board games like Hungry Hungry Hippo or Let’s Go Fishing. Players share the same field and directly compete against each other for the same ball or collection. Video Game examples: Arcade games like Pac-man, action computer games like Doom.

- Phased/Hybrid – These kinds of games come from Baseball, American Football, Tennis, and party games like Charades and Pictionary which combines Real-Time and Turn-Based styles of play. This can include paused-play and phased-turns. There are three examples of Phased/Hybrid games: 1) Archon had a strategic, turn-based layer at the board level and a real-time combat when pieces met each other on the same square. This is an example of layered-pacing where different layers of the game use different kinds of Pace. 2) Ultima IV where you can move, but there is a timing count-down where the game advances every so many seconds. This is an example of timed turn-based. 3) Baldur’s Gate had full-pause real-time combat allowing the player to savor the tactical planning that is resolved with real-time combat. This is an example of power-pausing where Real-Time pacing is accented with a generous, powerful pause feature that allows you to stop the action, queue up new commands, and then release the game to proceed.

In each of these types of Pace, it is Time that is being measured, and that alone is the enough to make it a game as defined by Play Motifs. I’ve posted over the years on my person blog (here, here, and here) that the Games Motif (called Playstates at the time) are the play/fun of measurement. When you add Time to any activity of play, you create a game. A jigsaw puzzle is the play of matching but if you were to add a time limit/tracker to that play, you have created a new style of play and it is what I would call a proper game.

Next, I introduce the second sub-aspect of Time is that of Length.

Length – This is the summed amount of time a player spends with a Video Game which can be measured from minutes to decades.

This sub-aspect has is define by advancements in save technology. While Video Games can be played in sessions that will vary in length played, from a few minutes to hours but carrying on a game between sessions requires some kind of saving method. Below I have established what I consider the five sub-aspects of Length that have occurred over the history of Game Development:

- Session Length – play lasted as long as a session which could be minutes to hours, but when finished the progress made is lost as there is no save function to continue. Example: Early computer games like Archon.

- Arcade Length – short, per transaction, multiple restarts per session, later arcade games incorporated pay to continue. Example: Arcade games like Pong and Pac-man. Gauntlet created the pay-to-continue practice.

- Campaign Length – play lasted as long as session but with the ability to continue in future sessions by saving the game. These kinds of video games are typically from the adventure & strategy & RPG genres and could continue for months to years. Example: Ultima IV and The Pawn.

- Indefinite Length – Play lasted from months to years to decades with Rougelikes and other ProcGen games, game with emergence. Example Rogue and Hades and Civlization series.

- Lifetime Hobby – A lifetime hobby, pretty exclusive in its demands on the player monopolizes as seen with eSports and MMOs and GaaS. Examples Guild Wars 2 and Counterstrike. These are games where the challenge is ongoing content delivery through DLC and expansions or intense skill development.

So this concludes the two sub-aspects of Time, and will now turn to what I call Endings, which is what determines when the play of a video game is considered to be over.

Endings:

If Time is about the sessions Length and Pace of play, then Endings is about the developer’s and player’s decisions about when a video game has ended. Even games that are indefinite in Length will have to contend with the player’s will to continue.

Endings have evolved from arcade, micro-transactions that are short play sessions to single game hobbies that can dominate a player’s life, including becoming a full-time profession for a rare few.

There are a range of different ways to determine when a game is ended and I’ve created the following listing or sub-aspects that tracks what I think are ways that games can end:

- Score-Threshold – A designer determined ending where first player to get to a particular score ends the game. Example: Pong, where players who are evenly matched can rally the ball between them indefinitely and the game ends only when the winning player reaches a score of 11.

- Time-Trial – A designer determined ending where the player fails to get the minimum or best result in a time trial. Example: Pole Position.

- No Lives Left – A designer determined ending where the player runs out of lives and the game ends. Example: Zaxxon, Breakout, and most arcade games.

- Countdown – A designer determined ending where the player needs to either complete the game or have the best score when the game’s timer countdown ends. Examples: Pitfall, Prince of Persia, and Challenge of the Five Realms.

- Finished – A designer determined ending where the player completes the video game’s end goal as typically found in adventure or campaign-based games. Examples: Ultima IV, Command & Conquer 3, and most adventure, RPG, and strategy games.

- ‘I’m Satisfied’ – A player determined ending where player has determined they have played enough of the video game to the point they feel like they’ve seen enough or ‘won it’ on their terms. The player feels that they’re satisfied and its time to move on. Examples: Sid Meier’s Civilization series can go on forever and most players will move on.

- ‘I’m Bored’ – A player determined ending where the player has decided its time to resign from the game because it no longer engages him/her. The player feels that they are bored and its time to move on. Many video games can be played forever and these run up against the player’s purely subjective boredom limit.

- ‘I’ve had a Celestial Discharge’– A player determined ending where the player can’t play video games any more because he/she has died. While it is morbid and silly to include this, in truth when a player dies, the play ends.

So this concludes the eight sub-aspects of Endings, and also concludes my Thoughts on Fundamentals two-post series. Next I’ll dive into the Game Element of Mechanics. I hope you come back to read that and thank you for your attention.